|

|

|

|---|

Monday, January 25, 2010

Ostensibly, it is about a US corporation that invades the planet Pandora in 2154 to extract a precious mineral - even if it has to displace the three-metre-tall blue people who live there. But yes, it's supposed to be a metaphor for the invasion of Iraq.

How can we be sure?

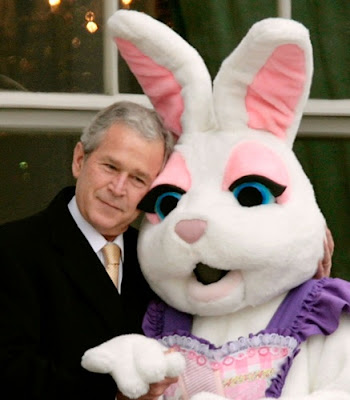

For a start, there are the clues in the dialogue, as subtle as toe-stubbing. The military commander of the earthlings echoes George Bush as he builds a rationale for first strike: "Our survival relies on pre-emptive action."

The earthlings' description of the assault as a "shock and awe" attack is a direct steal from the Pentagon's marketing line for its initial bombing of Baghdad. It's a reminder you just paid $18 to watch a commentary on US foreign policy (including 3D glasses).

The director spelt it out for us. Canadian-born James Cameron said last month: "We went down a path that cost several hundreds of thousands of Iraqi lives. I don't think the American people even know why it was done. So it's all about opening your eyes."

The movie succeeds in one kind of eye-opening. It cleverly transfers the viewer's empathy from the earthlings to the blue people. Cameron wants Americans - and, presumably, their British and Australian allies - to see their own side of the conflict from the viewpoint of the other: "We know what it feels like to launch the missiles. We don't know what it feels like for them to land on our home soil, not in America. I think there's a moral responsibility to understand that."

But Avatar fails to open anyone's eyes to the realities of the invasion of Iraq. If that is Cameron's aim, he has failed.

The invasion of Iraq was much worse. In Cameron's movie, the Americans are brutal but honest. They invade to extract the precious resource. The real-world Americans of the Bush invasion were utterly dishonest.

The Bush administration made two principal arguments for invading Iraq. One, that there was some collusion between the perpetrator of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda, and the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

There was no collusion. The men were enemies. But Bush pressed hard to confect some connection. On the day after the attacks, he grabbed his top counterterrorism official, Dick Clarke, as they left a meeting in the White House situation room. Clarke wrote in his 2004 book, Against All Enemies, that Bush said to him: "See if Saddam did this."

Clarke was surprised. He knew Bush had been told definitively by the intelligence services that al-Qaeda was responsible: "But, Mr President, al-Qaeda did this."

Bush: "I know, I know, but … see if Saddam was involved. Just look. I want to know any shred."

Bush had decided to invade Iraq long before the terrorists struck. September 11 was not the reason for the invasion; it was a political marketing opportunity. After all the rumoured and concocted connections were debunked, the pro-invasion hawks continued to press the theme. Bush's secretary of state, the prudent Colin Powell, cut all such references from drafts of his much-awaited speech to the United Nations Security Council, where he made the case for the invasion.

"Even after Powell threw material out, it would occasionally be quietly put back in," according to a 2004 book by the US intelligence expert, James Bamford, titled A Pretext for War.

A senior White House aide, Steve Hadley, sneaked the collusion claim back into the speech and, according to Bamford, when Powell got an admission from Hadley, he yelled at him "Well, cut it, permanently!"

What was left? Only the claim that Saddam was hiding weapons of mass destruction. Powell was foolish enough to make it, displaying artists' impressions of trucks he said were mobile germ-warfare labs, to his eternal chagrin. The invasion followed. Thousands of allied soldiers, and probably about 100,000 Iraqis to date, died as a result.

The WMD was an officially sponsored fiction. But the detailed story of how this claim was created and spun is extraordinary. In the journalist Bob Drogin's authoritative book, Curveball, he relates how the CIA director George Tenet assured Powell that their evidence was from an Iraqi defector who had worked on the WMD himself. The evidence supplied by the defector, codenamed Curveball, had been corroborated by three sources, Tenet said. Powell repeated this claim to the world.

After the invasion, the famous American weapons hound David Kay was tasked with finding the WMD. He asked the CIA about Curveball. What was he like to talk to? "Well, we've never actually talked to him," came the CIA reply. "You're kidding me, right?" Kay replied. But it was not a joke.

Curveball was in the hands of German intelligence. The Germans warned the CIA repeatedly that Curveball's evidence could not be verified. It turned out he was a liar. In the years he claimed to have been working on Saddam's secret WMD, he was actually driving a Baghdad taxi. Kay asked the CIA official about the three corroborating sources. "There really are no other sources," came the answer.

Filling out the picture of the Bush administration's betrayal of the US and its forces is the recent book by the journalist David Finkel, The Good Soldiers. It reports on a US infantry battalion in Iraq. Well-intentioned, hard-working, hopelessly uncomprehending, suffering bitterly, they, like the Iraqi people, were the ultimate dupes of the Bush-Cheney deception.

So Avatar doesn't tell us anything much about why the US invaded Iraq unprovoked. Or why its allies followed lamely along, in service of a lie. But it is in 3D.

Peter Hartcher is the Herald's international editor.